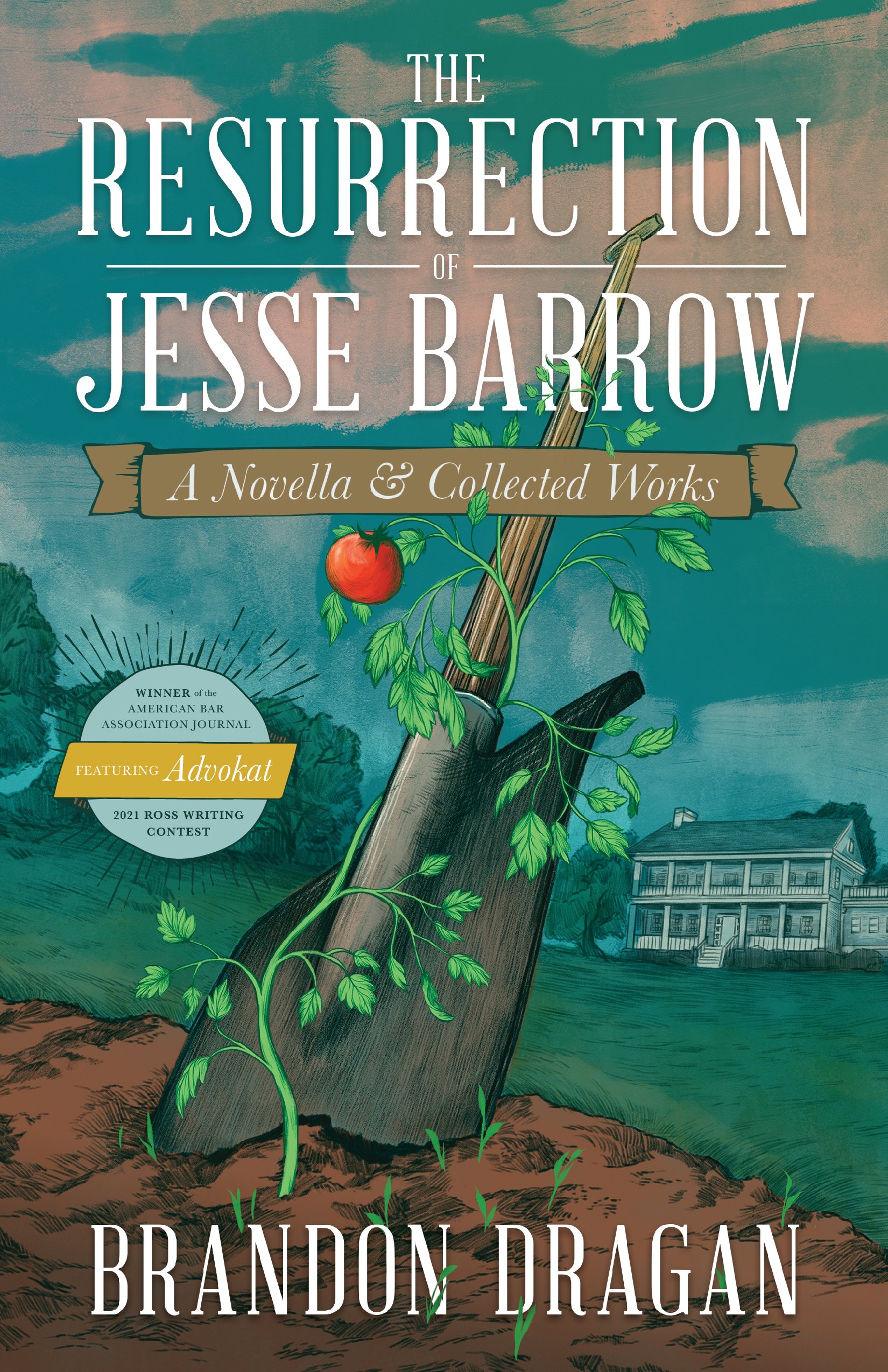

Folks in these parts like two things most of all: sausage and justice, though I reckon they wouldn’t much care to watch how either one is made.

– The Resurrection of Jesse Barrow

Spoiler alert… There is no town called Haywood, Alabama.

That being said, my vision for the world of Jesse Barrow grew out of some close friendships, two friends in particular who grew up in rural Alabama. Now, obviously these close friends weren’t around in 1911 rural Alabama, but as someone who studies history, I’ve always been fascinated by how our past affects our present. And the older I’ve become, the more I’ve been fascinated by how our present informs how we view our past, which then, paradoxically, informs our present. Both the past and the present can distort the truth.

What I mean by this is that typically yes, the victors write the history books. They tell us stories from their perspective. They might tell us how brave they were. They might tell us about all the good they did, the ways they changed the world for the better. And all of that might be true.

However, the victors are also likely to conveniently ignore any bad that they did.

But they wrote the books.

And the next generations read those books.

And now the present generation, living in the blessings of victory, begin to believe that they are superior to the “losers.”

This can happen because the victors’ grandkids read the stories written by the brave, good grandparents. It helps if the grandkids live in the lap of luxury, too.

As a result, the victors read greatness into the actions of their ancestors, and at the same time, read greatness into themselves.

And usually, such stories are not the whole truth.

I tried to tackle this paradox in The Resurrection of Jesse Barrow.

My perspective is a bit unique (although, it is probably becoming less so). I’ve lived in the south for nearly twenty years now, but I grew up in Northeastern New Jersey, the grandchild of immigrants from Eastern Europe. Those two elements of my identity combined to convince me from an early age that problems of race and injustice had nothing to do with me.

After all, I came from the part of the country that fought to free the slaves.

And on top of that, even if the United States had some culpability for slavery, my family wasn’t even here then, so I’m scot-free responsibility-wise.

And in a sense, that’s true.

My family never owned slaves. My family never belonged to a hate group.

Then, I moved to Nashville, Tennessee when I was 18.

And though I expected to find a den of overt racism, I discovered that in many ways, people were much more openly racist where I came from. Which got me questioning things. . .

As a northerner, I couldn’t be racist, right?

Because all the racists were in the south . . . right?

See… we northerners told ourselves a story after the war. We told ourselves that we were the good guys. We were the rescuers. We were the heroes. And in some sense, that’s not completely untrue. Scores and scores of men gave their lives for the freedom of others and in some sense that is surely noble.

However, that morphed through the years into stories about how bad other people were. And that in and of itself isn’t completely untrue.

Slavery was a detestable system that caused untold suffering and horror through the centuries. And there were people who benefited directly from that in the form of wealth and power.

But what I learned after moving to the south was that, a huge portion of the men who fought for the Confederacy didn’t own slaves. To be frank, many of them didn’t really have a dog in that fight (I say this, recognizing for many, a degree of culpability in fighting to preserve such an evil system).

My point is, I had learned that I was on the team of the “good guys” and those people down there were on the team of the “bad guys.”

Which morphed into a twisted belief—and this goes back to the days even before the war—that my side could not doing any wrong in comparison to the other side.

Sure, we might tell an ignorant joke here and there, but it was a joke! And nothing like what the other people did.

Sure, we might lock our doors when a person of color walks close to our car, but that’s just safety! And nothing like having different water fountains for different races!

Sure, our immigrant grandparents were able to save up and buy a house in a nice neighborhood, but that’s because they worked hard! And nothing like the privilege white people receive in the other place.

It took me a long time to start seeing that things were more complex than what I’d been taught. And when I learned that, I realized that indeed, I have been part of the problem.

Because it wasn’t just rich southerners who enjoyed the spoils of slave labor.

Manufacturers in the north, shipping magnates in the north, politicians in the north, factory workers in the north, and more all benefited from the same institution.

And the economic groundwork laid by that institution is the underpinning of the “great” American economy so many of us have enjoyed ever since.

So the truth is . . .

Directly or indirectly, I’ve benefited from the suffering of others.

Directly or indirectly, I’ve benefited from exploitation.

Directly or indirectly, my participation in the system as it exists makes me culpable.

The truth is . . .

I might love the country I live in, but if I’m honest, I haven’t wanted to really see how it was made.

The truth is . . .

We can all benefit from listening to the other.

We can all benefit from some humility.

We can all benefit from a new way of seeing ourselves.

Because the truth is . . . We all have a lot to learn.

- b